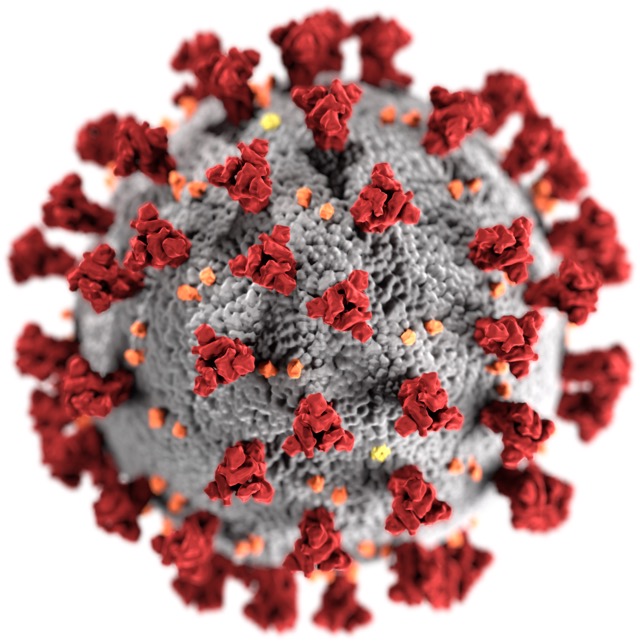

Low-income nations are grappling with escalating debt burdens and limited international support as the G20 has failed to mount a coordinated multilateral response comparable to its actions during the 2008 financial crisis.

Aggregate public debt in developing countries has reached 45 percent of GDP, with 43 percent now classified as in debt distress or at high risk, according to IMF figures. This represents an increase of nearly half since 2012, leaving nations such as Bangladesh and Ethiopia struggling with their obligations.

The G20’s debt relief initiative has fallen significantly short of expectations. The group agreed to temporary suspension of bilateral debt repayments for one year, yet only $5.3 billion has been suspended against an anticipated $11.5 billion.

Emerging economies within the G20 itself have experienced severe impacts. Brazil recorded capital outflows of $11.8 billion from its stock market between February and May, with a further $18.7 billion departing its bond market between February and April. Mexico saw $7 billion in capital flight during March alone, whilst both nations battled soaring infection rates.

This contrasts sharply with the robust domestic responses mounted by wealthy nations’ central banks and governments. The Federal Reserve made $2.3 trillion in loans available and expanded its securities portfolio from $3.9 trillion to $6.1 trillion between mid-March and mid-June through open-ended quantitative easing. The European Central Bank announced purchases of €120 billion under its existing Asset Purchase Programme and €1.35 trillion under its new Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme.

Fiscal measures proved equally substantial. The United States implemented stimulus exceeding $1 trillion. Germany unveiled two additional budgets totalling €156 billion and €130 billion, alongside €141 billion in direct local government support and €63 billion in state-level loan guarantees. The UK deployed £48.5 billion for public services, £29 billion for businesses and £8 billion for social safety nets.

The IMF and World Bank have increased their resources to an unprecedented $1 trillion in loans and non-conditional credit lines for developing countries. However, without G20 coordination of fiscal responses or ensuring robust multilateral financial safety nets are maintained, these measures may prove insufficient.

The group has struggled since 2017 with what observers describe as US reluctance to lead the global economic order established at Bretton Woods in 1944. This difficulty in securing American agreement to common agendas has resulted in effective inaction at the multilateral level.

The G20 has not coordinated policy action on movement of goods and people across borders, avoided bottlenecks in medical equipment supply, or prevented beggar-thy-neighbour measures. The group also failed to establish WHO as a permanent technical partner, with the Trump administration instead accusing the organisation of China bias and threatening membership withdrawal.

The consequences of this multilateral failure extend beyond immediate pandemic response. Developing and low-income countries face the prospect of accepting financially and politically onerous bilateral arrangements if multilateral institutions cease providing necessary safety nets or if major economies refuse debt relief offers.

The long-term impact on employment, education and social welfare in these nations will exceed the immediate health crisis effects, raising questions about whether the COVID-19 pandemic will further diminish developing countries’ already limited voices in international forums.